Trancoso and Belmonte

Trancoso is a tiny medieval village built within the walls of a castle. Today cars have access to the cobbled streets; however, the majority of the web of ancient lanes are so narrow that cars can barely squeeze through them.

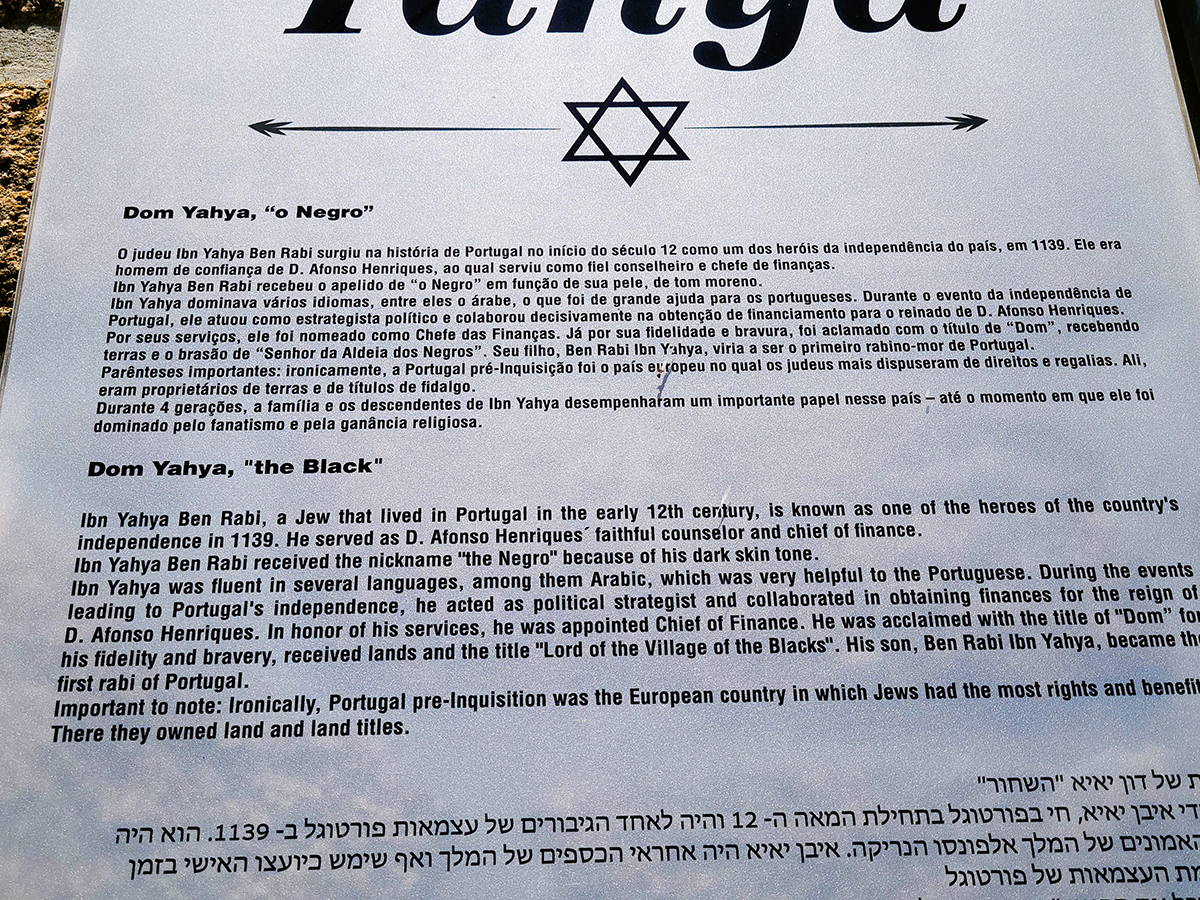

I had read about the Jews of Trancoso, who were a small, thriving population as early as the 12th century, and I was fascinated by their history.

Today there are no Jews in Trancoso. Many of them were murdered during the Inquisition, and a small number fled to safety. In 1497, those who stayed were baptized either voluntarily or involuntarily.

While outwardly adopting Catholicism within their homes, the “New Christians,” as they were called, continued to practice their ancient Jewish beliefs, traditions, and learnings.

The established trade fairs and geographical location of Trancoso enabled the New Christians, who were, by and large, well-educated, to create successful commercial networks within and beyond the borders of Portugal.

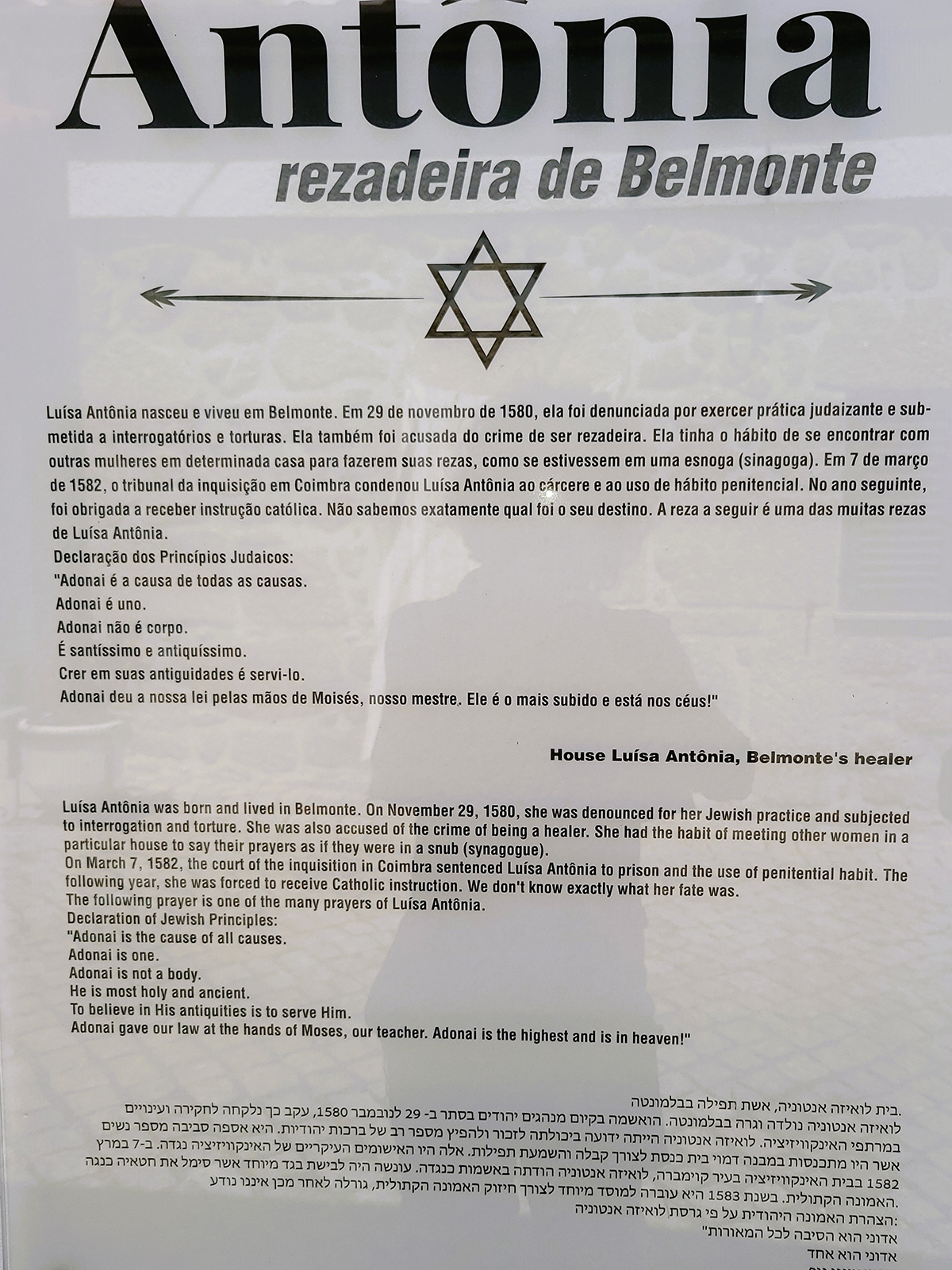

They secretly kept the Sabbath, lighting candles hidden in closets, and kept the Passover, Purim, and Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), celebrating these holy days not on the actual dates but several days before or after to avoid suspicion. It was primarily the women who passed down the ancient Jewish traditions for 500 years.

Lighting candles on Sabbath.

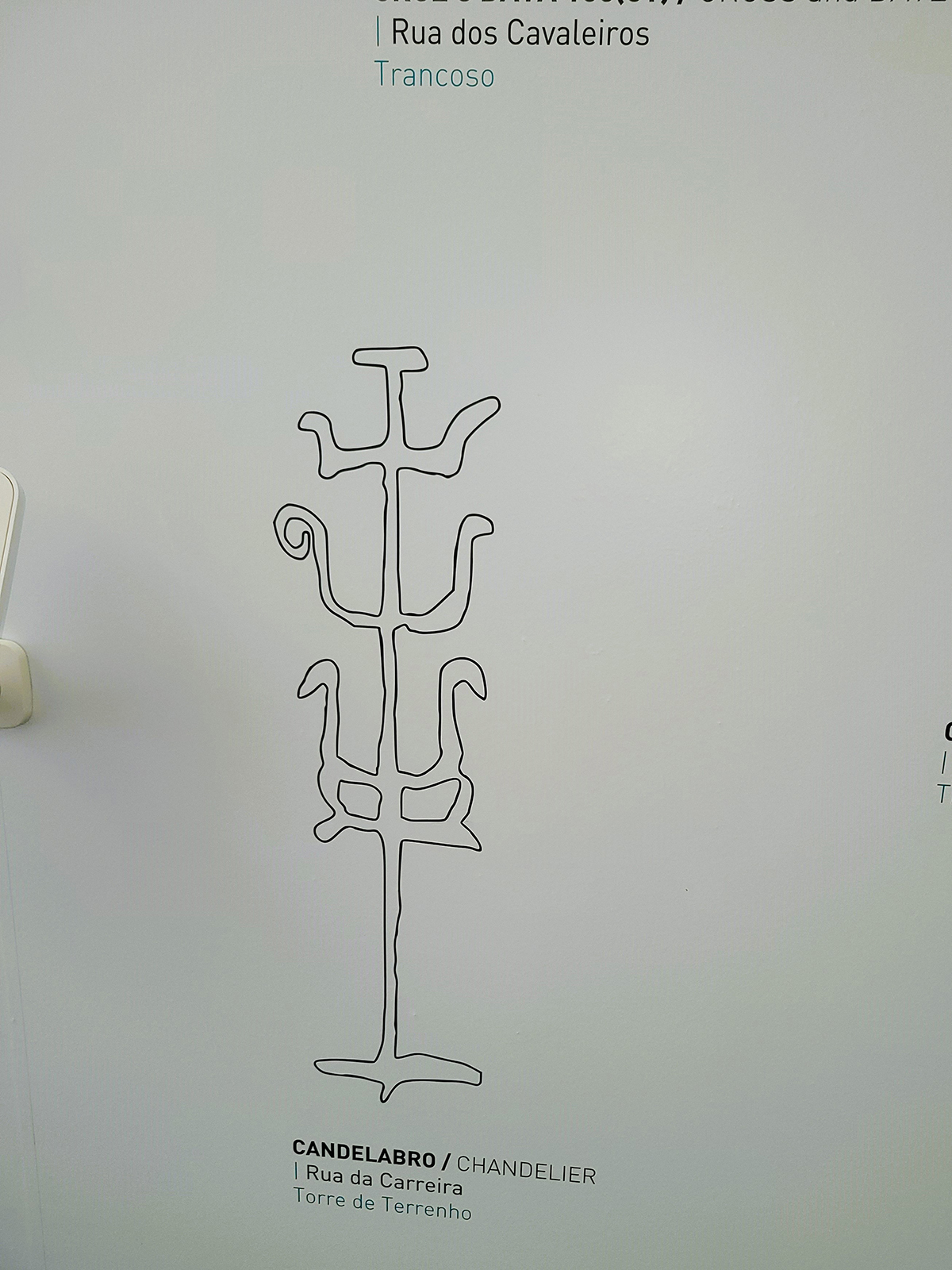

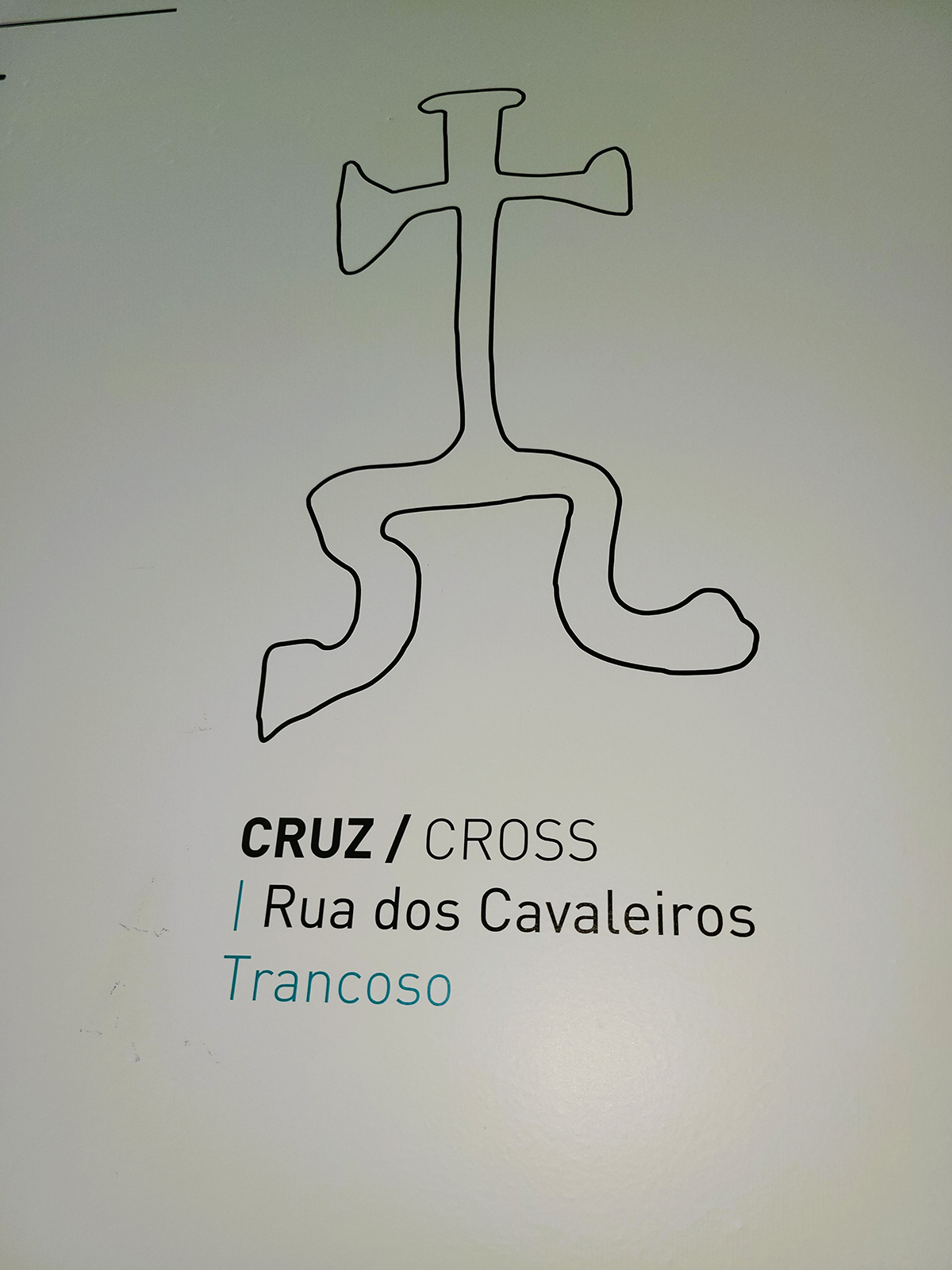

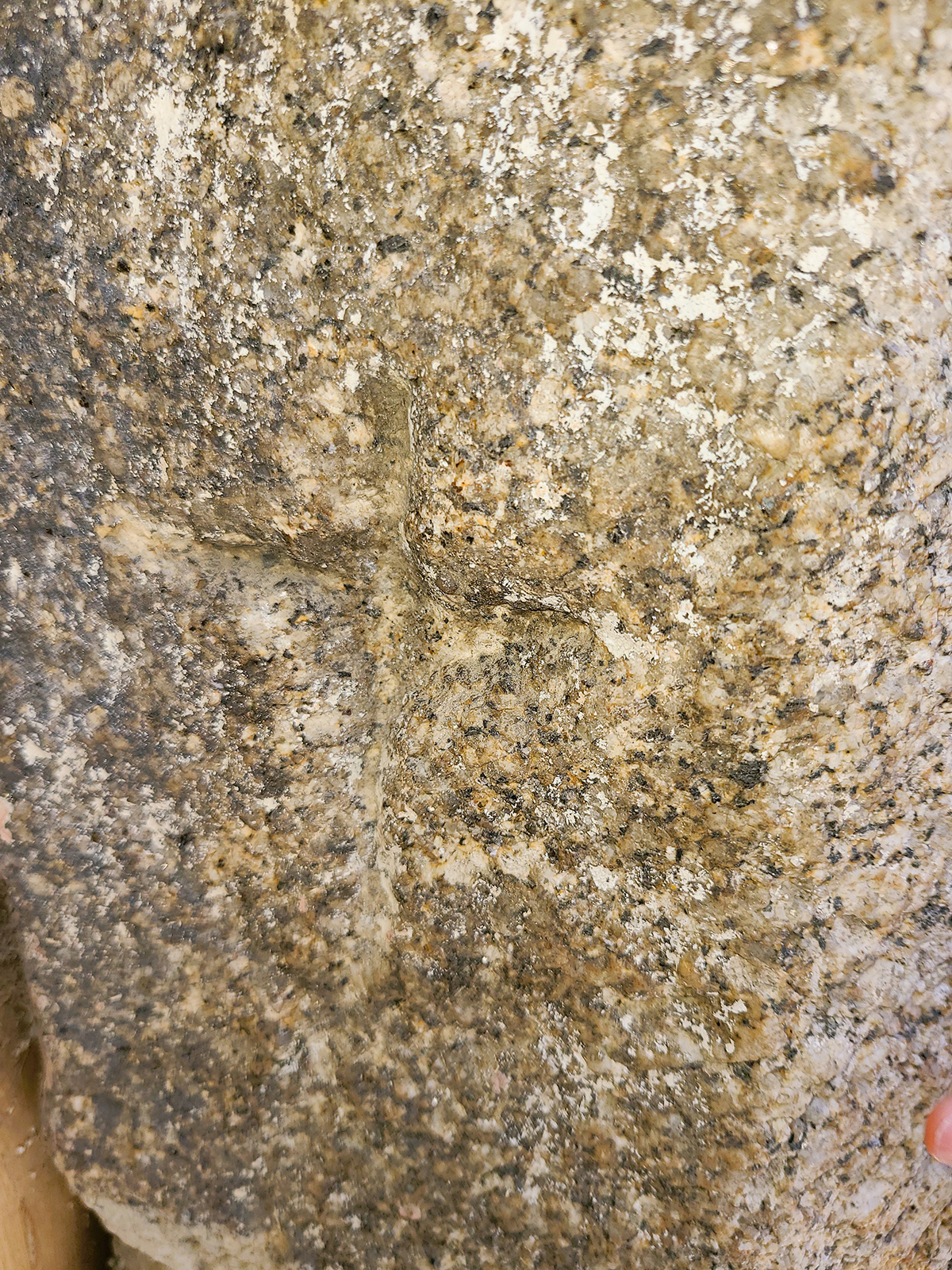

Lighting candles on Sabbath.Jewish families connected with other New Christians by marking a stone on the front of their homes with symbols they adopted from Christianity and Judaism -such as the cross and the menorah.

Finding the tiny Jewish Quarter was quite a challenge in the maze of winding lanes. We stopped into an optician’s shop to ask for assistance. Fortunately, he spoke French and pointed us toward the “Quartier Juif.” When we found ourselves on a narrow lane with abandoned little stone houses and warehouses, I peeked through a slit in the stone, and there stood a menorah with seven candle holders symbolizing the seven days of the creation of the universe or, as some believe, is a representation of “The burning bush,” when Moses heard the voice of God. It was typical for the Jews of Trancoso to decorate their homes with both Christian and Jewish artifacts to detract attention from their hidden religious beliefs.

Stone carved with a Crypto- Jewish symbol.

Stone carved with a Crypto- Jewish symbol. Stone houses and warehouses.

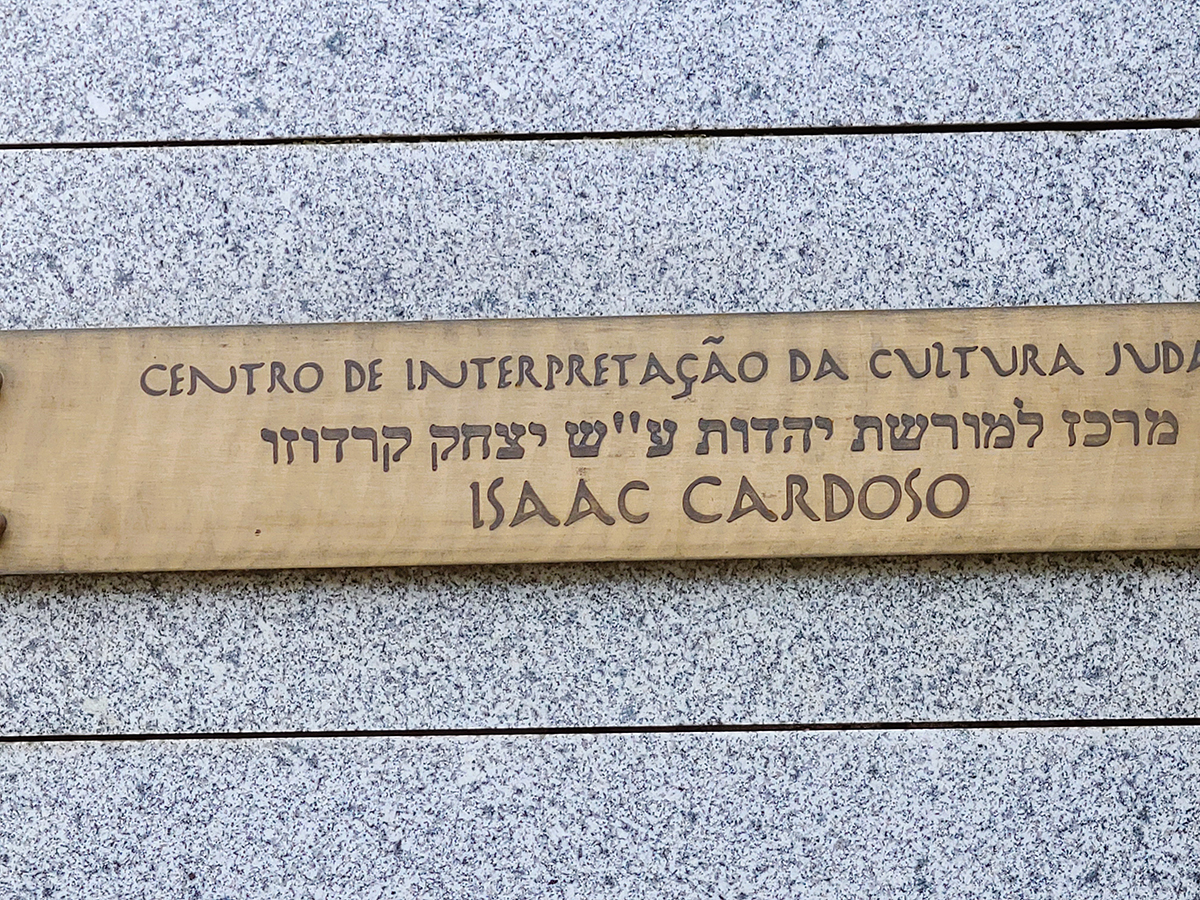

Stone houses and warehouses.At the end of the lane, we came across a glass-enclosed, locked, and bolted Jewish museum, the Isaac Cardoso Centre.

As we were preparing to leave, a young woman who spoke flawless English arrived, unlocked the doors, and took us on a tour of the museum and the small, recently built synagogue. Her great, great grandfather was a Crypto Jew. She is Catholic. Crypto-Judaism denotes secret adherence to Judaism while publicly professing to another faith, in this case, Catholicism.

Today the synagogue houses a Torah, which was brought back to Trancoso 500 years after the expulsion, and forced conversion of the Jews in 1947.

The outside door of the synogogue set into ancient stones.

The outside door of the synogogue set into ancient stones. The memorial room in the museum with the names of the Jews of Trancoso.

The memorial room in the museum with the names of the Jews of Trancoso. The Synogogue within the walls of the museum completed in 2012.

The Synogogue within the walls of the museum completed in 2012.Before leaving Trancoso, we found a coffee and pastry shop in the central square within the ancient walls, where we lingered over coffee and the traditional pastry for which Trancosa is famous: Sardinhas Doces, an extremely sweet pastry in the shape of a fish, made with a thin dough, which is wrapped around a filling consisting of egg yolks, ground almonds, sugar, and cinnamon.

Onwards to Belmonte, where a small community of Crypto Jews exists to this day.

Belmonte

A 13th-century castle towers over Belmonte from a hilltop with a view of a vast, fertile landscape of cultivated fields, vineyards, neighboring communities, and rolling hills carpeted in spring flowers.

We set out on a crisp, sunny spring morning to wander through the parks, the narrow winding medieval streets, and the churches that populate this charming town with an interesting history.

Belmonte was the home of Pedro Alvares Cabral, born in 1467. At the young age of thirty-two, Cabral led a fleet of thirteen ships and over a thousand men on a six-week journey ending off the coast of Brazil. He was the first explorer to reach South America. He also reached Europe, North America, Asia, Africa, and India via the Cape of Good Hope. A statue honoring Belmonte’s famous son stands in the center of a landscaped park where he is surrounded by trees and blooming flowers.

Our wandering led us past the Olive Museum, which displays an old wine press and offers an assortment of local Belmonte products, from olive oil and wine to jams.

The Jewish Museum sits nestled among the zig-zag lanes of the historical Jewish Quarter. There, we met up with our charming and knowledgeable guide, who was born and raised in Belmonte.

In 1492, during the Spanish Inquisition, Jews were expelled from Spain when the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I of Castile, feared that the flourishing Jewish population would become more powerful than them. Many Spanish Jews fled to Portugal. However, in 1497 the King of Portugal issued an edict expelling the Jews even though they played a vital role in the economy and prosperity of the country.

Jews were forced to either convert to Catholicism or leave Portugal. The new Christians, as they were called, preserved their traditions secretly behind closed doors while outwardly observing Christianity. They prayed in Portuguese, adopted Christian names, and outwardly observed all Christian religious holidays. Jewish prayers and beliefs were passed down orally from generation to generation. When they entered the church for weddings, funerals, and baptisms, which they were compelled to observe as Catholics, they would recite this silent prayer: “In here comes my body but not my soul, nor my heart.”

Before attending church, these significant events were observed in the secrecy of their homes according to Jewish traditions.

For five hundred years, they hid their forbidden religion, intermarried, and kept their devotion to Judaism alive, observing the Sabbath, Passover, Channukah, and Purim, and even a form of Kashrut dietary laws. They believed that they were the only surviving Jews.

The Mezuzah was hidden indoors.

The Mezuzah was hidden indoors. The stone next to the front door with a Symbol showing that they were Crypto Jews.

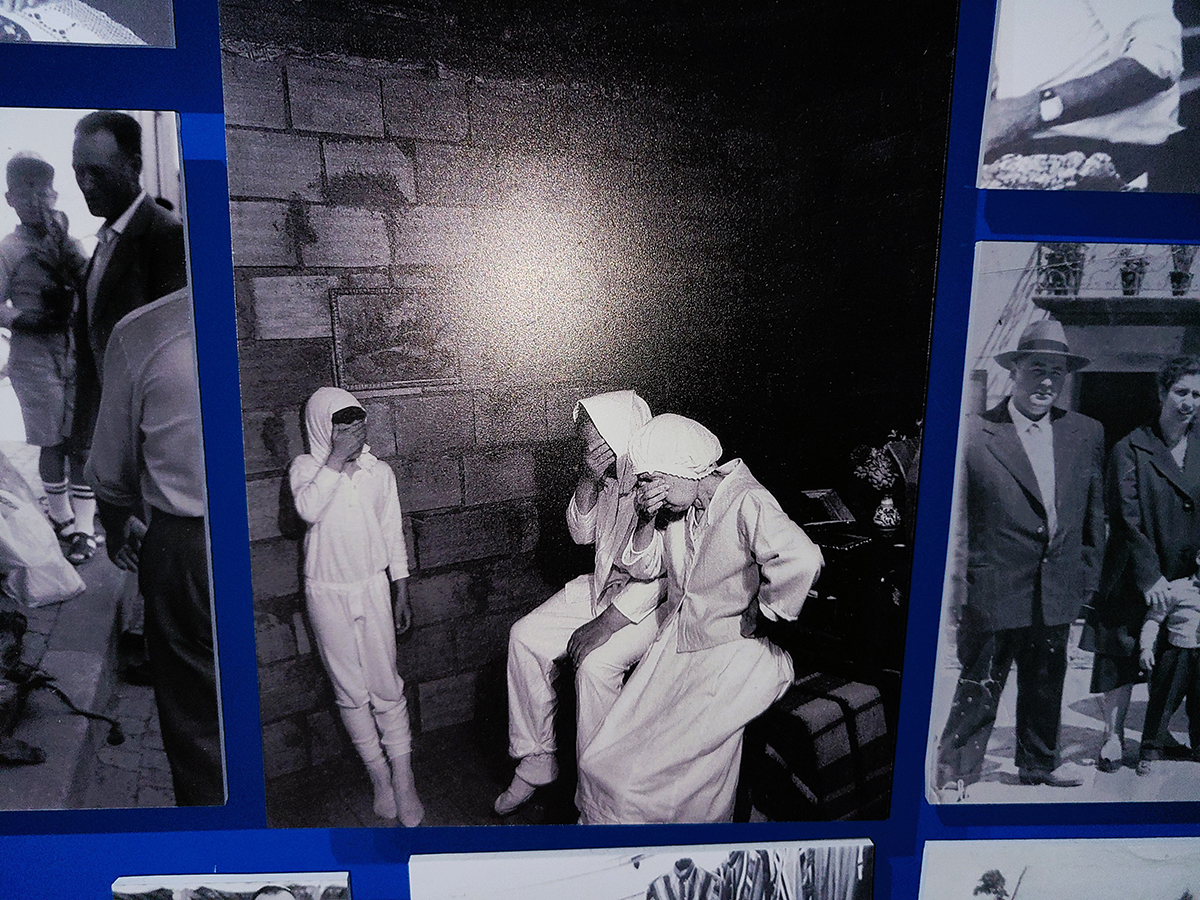

The stone next to the front door with a Symbol showing that they were Crypto Jews. On Passover they wore white Clothing

On Passover they wore white Clothing Baking Matzah. A jug for water, a bowl, a cup to bake the dough, and roof tiles for cooking

Baking Matzah. A jug for water, a bowl, a cup to bake the dough, and roof tiles for cookingIn 1917, Samuel Schwarz, a Jewish mining engineer from Poland, arrived in Belmonte to work in the tin mines. He observed that the New Christians had some unusual habits. Schwarz sought out the oldest New Christian in the town, a woman in her late eighties. In her presence, he recited the Jewish prayer: “Shema Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu Adonai Echad.” When he said Adonai-God, she covered her eyes. A clear sign to Schwarz that there had to be Jewish history hidden in Belmonte.

In 1974 when the dictator Salazar’s rule ended in Portugal, the Crypto Jews began to emerge from secrecy.

Today, a huge menorah stands in the plaza of the old Jewish Quarter, where the entire community, Jews and non-Jews alike, come out to celebrate Channukah.

Shabbat and Jewish holidays are no longer a secret. Tourists flock from around the world to visit this little town. Men proudly wear kippot (head coverings), and women put their husband’s tallaisim (prayer shawls) on outdoor washing lines to dry.

Bet Eliahu synagogue was inaugurated in December 1996, five hundred years after the edict of expulsion proclaimed in 1497.

A Menorah stands proudly overlooking the valley below Belmonte.

A Menorah stands proudly overlooking the valley below Belmonte.In 2022 when we visited, it was estimated that there are approximately forty-five Jews now living in Belmonte. In 1989 they were recognized by the Orthodox Jews of Israel as Jews, and many began emigrating to Israel – a five-hundred-year dream come true!

They covered their eyes when they said Adonai

They covered their eyes when they said Adonai